A federal court judge in Texas recently granted the defendant’s motion for judgment on the pleadings, finding that the plaintiff was barred from asserting that the defendant’s smartphone apps infringed the plaintiff’s patent.

The case of Lighthouse Consulting Group, LLC v. BB&T Corp. involved patents for a system for remote depositing negotiable financial instruments, such as personal checks.

The plaintiff claimed that the remote check deposit features available in defendants’ smartphone banking apps infringed certain claims in the patents. The plaintiff alleged that the defendants infringed the claim element of a “carrier designed to permit a front and back image” of checks under the doctrine of equivalents.

The “doctrine of equivalents” allows a court to hold a defendant liable for patent infringement even though the infringing device or process doesn’t fall within the literal scope of a patent claim but is still equivalent to the claimed invention.

Judge Learned Hand wrote that the purpose of the doctrine was “to temper unsparing logic and prevent an infringer from stealing the benefit of the invention.”

USAA Capital Corporation, one of the defendant banks in the Lighthouse case, filed a 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss Plaintiff’s claims. Rule 12(b)(6) allows a party to raise the defense that the complaint “fail[s] to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.”

USAA argued that the plaintiff was barred by prosecution history estoppel from using the doctrine of equivalents to claim infringement of the “carrier” element of the patent claims.

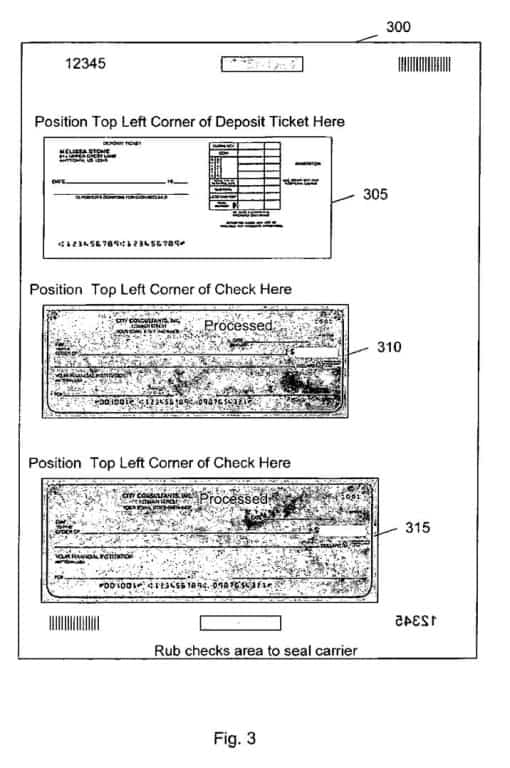

The “carrier” in the plaintiff’s patent was a physical object, such as “a non-reusable, self-adhesive transparent, flexible, non-glare two-sided” plastic sleeve-type object, as shown in the drawing above. USAA argued that the term “carrier” could not be construed to include non-physical computer software.

The defendant argued that the plaintiff was barred from claiming infringement of either patent under the doctrine of equivalents due to prosecution history estoppel. Prosecution history estoppel can occur in two ways. Either:

1. by making a narrowing amendment to the claim (“amendment-based estoppel’) or

2. by surrendering claim scope through argument to the patent examiner (“argument-based estoppel”).

Under the case of Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., “patentee’s decision to narrow his claims through amendment may be presumed to be a general disclaimer of the territory between the original claim and the amended claim.”

During the prosecution of one patent application, the examiner repeatedly rejected the plaintiff’s claims in view of the prior art. In response, the plaintiff amended the claim to require an identifier “on the front side and back side of the carrier.” The defendant argued that this narrowing amendment surrendered of all equivalents that didn’t include an identifier on a front and back side of a physical “carrier.”

Plaintiff argued that an exception under Festo allowed a finding of infringement under the doctrine of equivalents because the defendants’ banking apps were “after-arising technology” that were unforeseeable at the time of the patent application.

The court noted that the date of the patent’s latest amendment, not its filing, determined the period of foreseeability. In this case, the patent at issue was amended in 2010, and mobile apps for remote deposits were introduced before this date.

The judge thus dismissed the case.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.