The Federal Circuit has denied a petition for a rehearing of its February decision reversing the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejection of registration for the proposed mark “TRUMP TOO SMALL.”

In 2018, Steve Elster sought to register the phrase “TRUMP TOO SMALL” in standard characters for use on shirts in International Class 25. The class of goods encompasses:

Shirts; Shirts and short-sleeved shirts; Graphic T-shirts; Long-sleeved shirts; Short-sleeve shirts; Short-sleeved shirts; Short-sleeved or long-sleeved t-shirts; Sweat shirts; T-shirts; Tee shirts; Tee-shirts; Wearable garments and clothing, namely, shirts. . . .

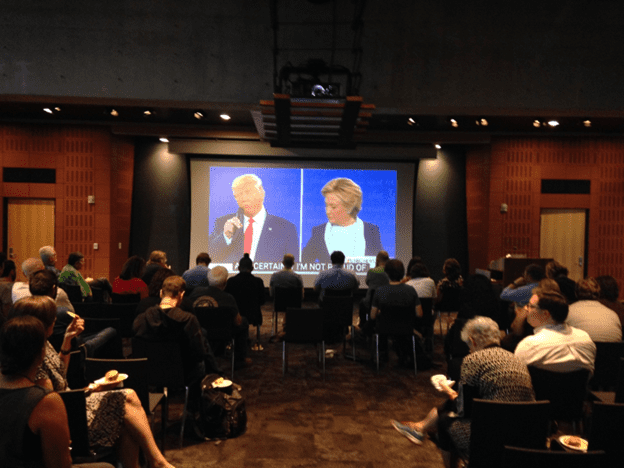

According to Elster’s registration request, the phrase he sought to trademark invokes an exchange between President Trump and Senator Marco Rubio from a 2016 presidential primary debate, and aims to “convey[] that some features of President Trump and his policies are diminutive.”

As NBC News reported at the time,

In response to the property mogul calling him “little Rubio,” Rubio conceded that Trump was taller than him. However, the Florida senator suggested Trump had small hands for his height.

“And you know what they say about guys with small hands,” Rubio said with a smile, prompting stunned laughter from the crowd.

After a brief pause, he added: “You can’t trust ’em!” The crowd responded with applause.

The USPTO examiner rejected the proposed mark on two grounds.

First, the examiner concluded that the mark was not registrable because section 2(c) of the Lanham Act bars registration of a trademark that “[c]onsists of or comprises a name . . . identifying a particular living individual” without the individual’s “written consent.”

The examiner concluded that it didn’t matter that the mark was “intended as political commentary” because there is no statutory or “case law carve[] out” for “political commentary.”

As the court noted,

The examiner rejected Elster’s contention that denying the application infringed his First Amendment rights, finding that the registration bars are not restrictions on speech, and in the alternative, that any such restriction would be permissible.

Also, the examiner denied registration of the mark under the Lanham Act section 2(a)’s false association clause, which bars registration of trademarks that “falsely suggest a connection with persons, living or dead.”

Elster appealed to Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB), arguing that sections 2(c) and 2(a) constituted impermissible content-based restrictions on speech under the First Amendment.

The TTAB concluded that section 2(c) wasn’t an unconstitutional restriction on free speech.

The Federal Circuit noted that a trademark represents “private, not government, speech” entitled to some form of First Amendment protection.

It discussed two recent US Supreme Court trademark decisions, which each relied on a “core postulate of free speech law”—that “[t]he government may not discriminate against speech based on the ideas or opinions it conveys”….

It didn’t matter that Elster planned to sell his shirts, said the court:

It is well established that speech ordinarily protected by the First Amendment does not lose its protection “because the [speech] sought to be distributed [is] sold rather than given away.”

The court also noted that “the right to criticize public men” is “[o]ne of the prerogatives of American citizenship.”

The question here said the court,

is whether the government has an interest in limiting speech on privacy or publicity grounds if that speech involves criticism of government officials— speech that is otherwise at the heart of the First Amendment.

The court noted that

there can be no plausible claim that President Trump enjoys a right of privacy-protecting him from criticism in the absence of actual malice—the publication of false information “with knowledge of its falsity or in reckless disregard of the truth.”

Also,

The government, in protecting the right of publicity, also has an interest in preventing the issuance of marks that falsely suggest that an individual, including the President, has endorsed a particular product or service. But that is not the situation here. No plausible claim could be or has been made that the disputed mark suggests that President Trump has endorsed Elster’s product.

The court concluded:

The PTO’s refusal to register Elster’s mark cannot be sustained because the government does not have privacy or publicity interest in restricting speech critical of government officials or public figures in the trademark context—at least absent actual malice, which is not alleged here.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.