The Federal Circuit has reversed a district court’s ruling that a patent’s claims were indefinite and thus that the patent was invalid.

Sonix Tech. Co., Ltd. v. Publ’ns Int’l, Ltd. is a case involving Sonix’s patent for a system and method for using a “graphical indicator” (e.g., a matrix of small dots) to encode information on the surface of an object.

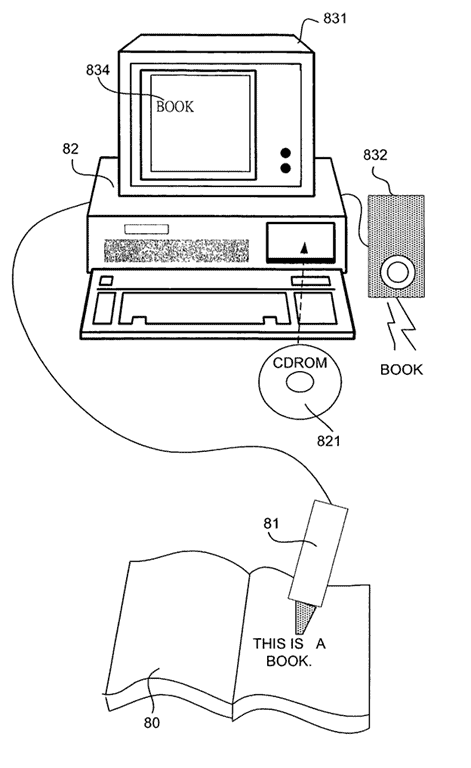

The dots can be arranged in a matrix, and each cell in the matrix either contains or doesn’t contain a dot, “resulting in a unique pattern that can store information.”

For example, the system can be used with an optical device to “read” information in a children’s book.

The Federal Circuit noted that

Of course, encoding information on the surface of an object is not new. The ’845 patent admits that information has been recorded on the surface of objects “[d]ating back to ancient time[s],” … and lists a bar code as a “conventional” example of a graphical indicator, … The ’845 patent purports to improve on conventional methods by rendering the graphical indicator “visually negligible.”

In 2010, Sonix claimed that children’s books using dot patterns produced by GeneralPlus, a Taiwanese company, infringed the ’845 patent. In response, the defendant’s parent company requested an ex parte reexamination of the patent.

The case turned on whether the phrase “visually negligible” was indefinite, because “it depends on the visual acuity of the observer.’”

The district court

rejected Sonix’s argument that “visually negligible” means “something that may be visible, but does not interfere with the user’s perception of other visual information on a surface,” concluding that defining the term “as reliant on the user’s perception provides no objective standard by which to measure the scope of the term—the user’s perception becomes the measure and this is insufficient.”

However, the Federal Circuit agreed with Sonix that

a skilled artisan would understand, with reasonable certainty, what it means for an indicator in the claimed invention to be “visually negligible.”

The Federal Circuit noted that:

Because language is limited, we have rejected the proposition that claims involving terms of degree are inherently indefinite. … Thus, “a patentee need not define his invention with mathematical precision in order to comply with the definiteness requirement.”