The Federal Circuit has ruled that the claims of software patents for synchronizing the lip movements of animated characters are not abstract.

The case of McRo, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America involved methods for 3-D animation.

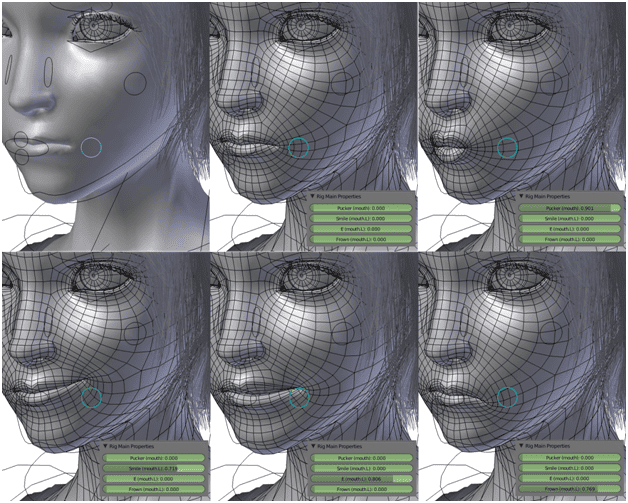

The “neutral model” of an animated character’s face shows the neutral, resting facial expression. Other models of the face are called “morph targets.” Each one represents the face as it makes a certain sound.

The representation of a face making a sound is called a “viseme.”

Traditionally, animators would have to manually manipulate a character model “until it looked right—a visual and subjective process” — and a tedious and time-consuming one.

The patents aimed to automate the task by applying a set of rules.

McRo filed suit against a large number of video game companies, including Bandai, Sega, Caprom, and Sony, for infringement of the patents.

The defendants argued that the asserted claims were unpatentable.

The district court agreed, because the claims weren’t limited to specific rules for the process but “purport to cover all such rules.”

while the patents do not preempt the field of automatic lip synchronization for computer-generated 3D animation, they do preempt the field of such lip synchronization using a rules-based morph target approach.

In other words, the court ruled that by trying to claim a patent on a ruled-based approach for synchronization, the invention was claimed too broadly.

The district court determined that one claim of one of the patents was

drawn to the [abstract] idea of automated rules-based use of morph targets and delta sets for lip-synchronized three-dimensional animation.

But the Federal Circuit disagreed.

The court noted that

concern arises when the claims are not directed to a specific invention and instead improperly monopolize “the basic tools of scientific and technological work.”

But the court found that the process previously used by the human animators wasn’t the same as the process required by the patent claims.

Defendants concede an animator’s process was driven by subjective determinations rather than specific, limited mathematical rules. The prior art “animator would decide what the animated face should look like at key points in time between the start and end times, and then ‘draw’ the face at those times.” … The computer here is employed to perform a distinct process to automate a task previously performed by humans.

The court thus concluded that the challenged claim was not directed to an abstract idea (i.e., that of rule-based lip synching) and it reversed the district court’s ruling for the defendants.

Takeaway

Although many software-related patent claims have been rejected in recent years, this case shows that software patents are far from dead.

A key issue here is that the computer wasn’t simply automating a set of rules that were already in use (as in previous cases rejecting software patent claims). Here, the computer was applying new rules to better perform a task that was previously done manually.