NPR’s Planet Money podcast recently reported on how the Hydrox cookie — and the Hydrox trademark — were resurrected after years of obscurity.

As the podcast noted,

A trademark is a funny kind of property. It’s different from a patent, it’s different from owning the rights to a song. A trademark can be a single word, a slogan, a logo. It isn’t owning the business, it’s owning the things that make the business distinct and recognizable, what sets it apart. Trademarks serves two purposes: To prevent confusion for consumers, and to discourage knock-offs. You can think of it as a relationship between a company and its customers. It’s a signal that tells people buying a product: We made this, and it’s legit.

When a company stops using a trademark, it’s considered abandoned. At that point, anyone else can reclaim it.

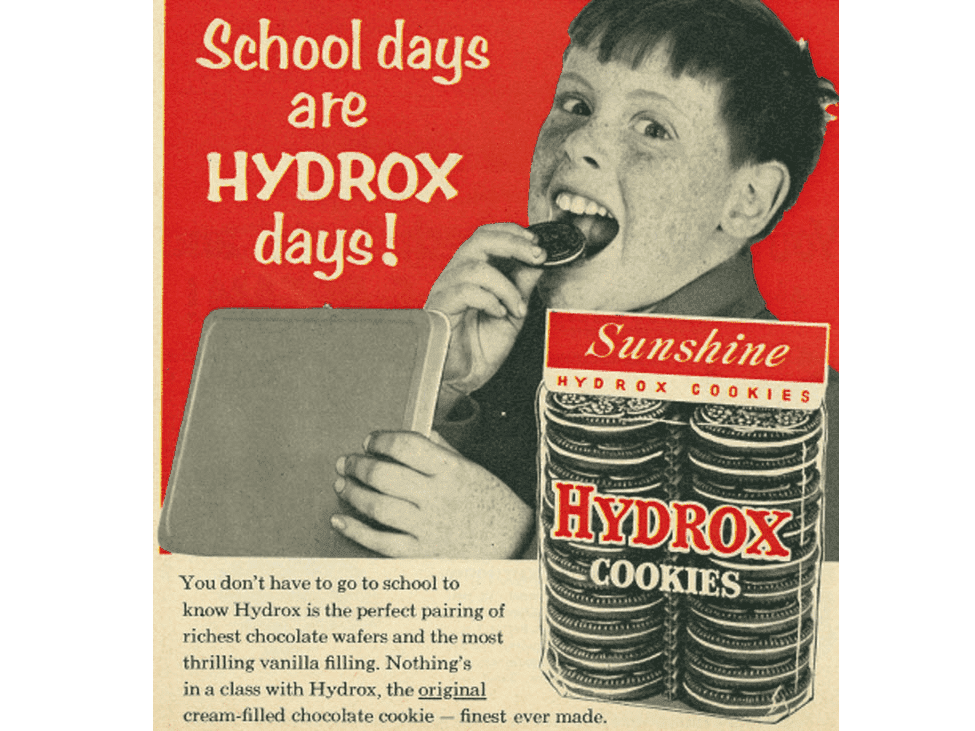

As NPR reported, Hydrox cookies look like Oreos but the brand is older — introduced in 1908. (Oreos, by the way, are reportedly the best-selling cookies in the world.)

Hydrox cookies — which fans consider superior to Oreos — were discontinued in 1999.

Ellia Kassoff grew up with Hydrox cookies and was disappointed to see them disappear from stores.

The Hydrox trademark had been passed on to Kellogg’s, and when Kassoff wrote to Kellogg he was told that the company had no plans to reintroduce the cookies.

Kassoff forwarded that letter to the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) as evidence that the mark had been abandoned. When the USPTO agreed, Kassoff then reclaimed the Hydrox mark for himself.

His next task was to recreate the actual cookie. He hired a South Carolina food scientist who also grew up with Hydrox cookies and knew what they were supposed to taste like.

The next-generation Hydrox cookies are now sold on Amazon and in 4,000 US stores.