At a recent live stream presentation sponsored by the Center for Intellectual Property Understanding (CIPU) and The Institute for Business Innovation (IBI) at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, Professor Dan Brown of Northwestern University said “The world is unaware of the cannibalistic nature of the current IP system and what it means for innovation and jobs.”

What did Prof. Brown, who is also an inventor with more than 40 patents, mean by that?

Brown explained:

We have failed to support the rights of the inventor. Providers of look-alike products, both domestic and foreign, are engaged in theft but not held accountable. It is more efficient to infringe or steal someone’s work than to spend the time and money to develop it yourself. The chances of being caught and punished are much more unlikely today than a decade ago.

Brown has contributed to the fight against COVID-19 with his patent-pending “InstaShield” that can be attached to a baseball cap to protect the wearer’s face. His company was able to put the shields into production within six weeks of him coming up with the idea, and it now produces 50,000 shields per day. For each shield sold on its website, the company donates one to an essential worker or senior.

Brown pointed out that without patent protection his company wouldn’t have been able to take the risk of making the six-figure investment required to put the shields into production so quickly.

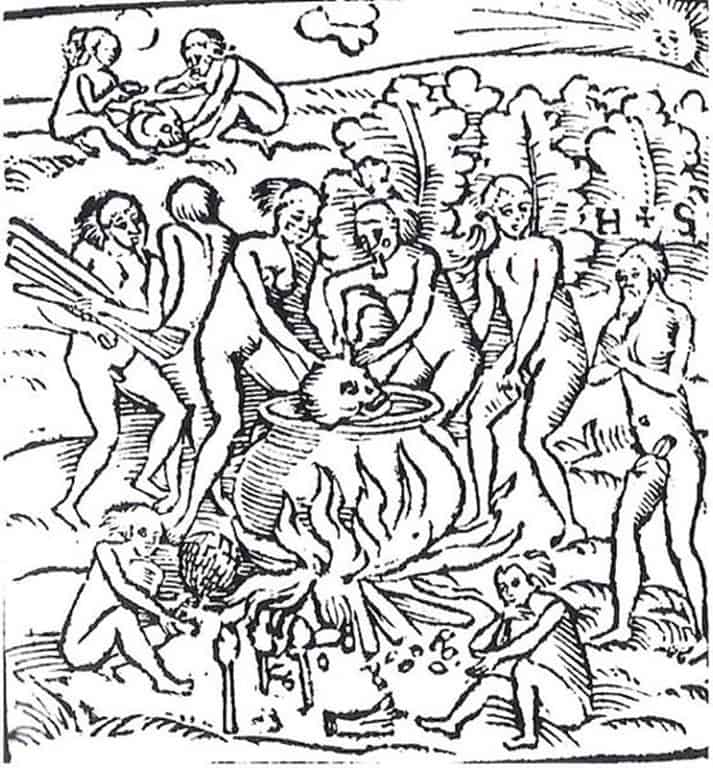

“If we can’t protect our products against the knockoffs in the marketplace, it becomes a cannibalistic system,” he said.

“We have an efficient infringement model where small companies get knocked off all the time because the people who knock you off do not get held accountable.”

“How can we sustain an American-made business model if we allow cannibalism of those new ideas?… We need reform in the patent office, we need reform in the court system.”

A New York Times op-ed may have coined the term “efficient infringement” about five years ago. As Joe Nocera wrote, “efficient infringement” is the

relatively new practice of using a technology that infringes on someone’s patent, while ignoring the patent holder entirely. And when the patent holder discovers the infringement and seeks recompense, the infringer responds by challenging the patent’s validity.

As one law school blog commented,

In a nutshell, efficient infringement occurs when a company deliberately chooses to infringe a patent given that it is cheaper than to license the patent. The reason it is cheaper is what makes it hard to explain briefly: a slew of legal changes to the patent system by Congress, courts, and regulatory agencies in the past ten years have substantially increased the costs and uncertainties in enforcing patents against infringers.

Nocera continued,

Should a lawsuit ensue, the infringer, often a big tech company, has top-notch patent lawyers at the ready. Because the courts have largely robbed small inventors of their ability to seek an injunction — that is, an order requiring that the infringing product be removed from the market — the worst that can happen is that the infringer will have to pay some money. For a rich company like, say, Apple, that’s no big deal.

As The Economist noted, recent patent law reforms “have strengthened the position of big firms in relation to the little guy”:

Christopher Coons, a Democratic senator critical of the rule changes, has spoken of a “steady erosion of patent rights”. Worse, Mr Coons has argued, they create perverse incentives for big companies to flout patents. Boris Teksler, Apple’s former patent chief, observes that “efficient infringement”, where the benefits outweigh the legal costs of defending against a suit, could almost be viewed as a “fiduciary responsibility”, at least for cash-rich firms that can afford to litigate without end.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.