The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has ruled that state law right-of-publicity claims are pre-empted by the federal Copyright Act “when a likeness has been captured in a copyrighted artistic visual work and the work itself is being distributed for personal use.”

The case of Maloney v. T3 Media, Inc .was brought by former student athletes Patrick Maloney and Tim Judge. Maloney and Judge played for the Catholic University men’s basketball team between 1997 and 2001.

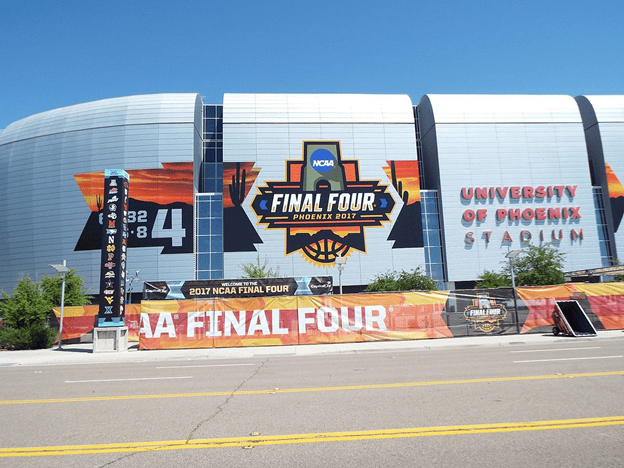

In their first year on the team, the men made it to the Division III national championship game, which their team won in an upset.

The game was captured in a series of photographs, including some showing the plaintiffs. The NCAA owns the copyright to these photos and placed them in its collection, the NCAA Photo Library.

T3Media is a company that provides storage, hosting, and licensing services for digital content, including photos. In 2012, T3 made a deal with the NCAA to store and license the images in the NCAA Photo Library.

Consumers can view the NCAA photos on the site Paya.com and get a license to download one for $20 to $30.

The plaintiffs sued, on behalf of themselves and “all current and former NCAA student-athletes whose names, images, and likenesses have been used without their consent by [T3Media].”

The complaint asserted claims for violation of California’s statutory right of publicity, common law right of publicity, and Unfair Competition Law.

T3Media argued that the federal Copyright Act preempted the claims and that the claims were barred by the First Amendment. T3 also argued that California’s statutory exemption for news, public affairs, or sports broadcasts or accounts precluded liability for any publicity-right violations.

The district court agreed with T3 and the plaintiffs appealed.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit held,

our cases clarify that a publicity-right claim may proceed when a likeness is used non-consensually on merchandise or in advertising. But where a likeness has been captured in a copyrighted artistic visual work and the work itself is being distributed for personal use, a publicity-right claim is little more than a thinly disguised copyright claim because it seeks to hold a copyright holder liable for exercising his exclusive rights under the Copyright Act

The court also noted that:

Section 301 of the [Copyright] Act seeks “to preempt and abolish any rights under the common law or statutes of a State that are equivalent to copyright and that extend to works,” so long as the rights fall “within the scope of the Federal copyright law.”

Thus, the court held that the plaintiffs’ state law publicity claims were preempted by federal copyright law.