The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has published new Guidelines for Assessing Enablement in Utility Applications and Patents in View of the Supreme Court Decision in Amgen Inc. et al. v. Sanofi et al.

The Guidelines are for ascertaining compliance with the enablement requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112. This requires that a patent specification enables a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA) to make and use the invention.

As the USPTO explains,

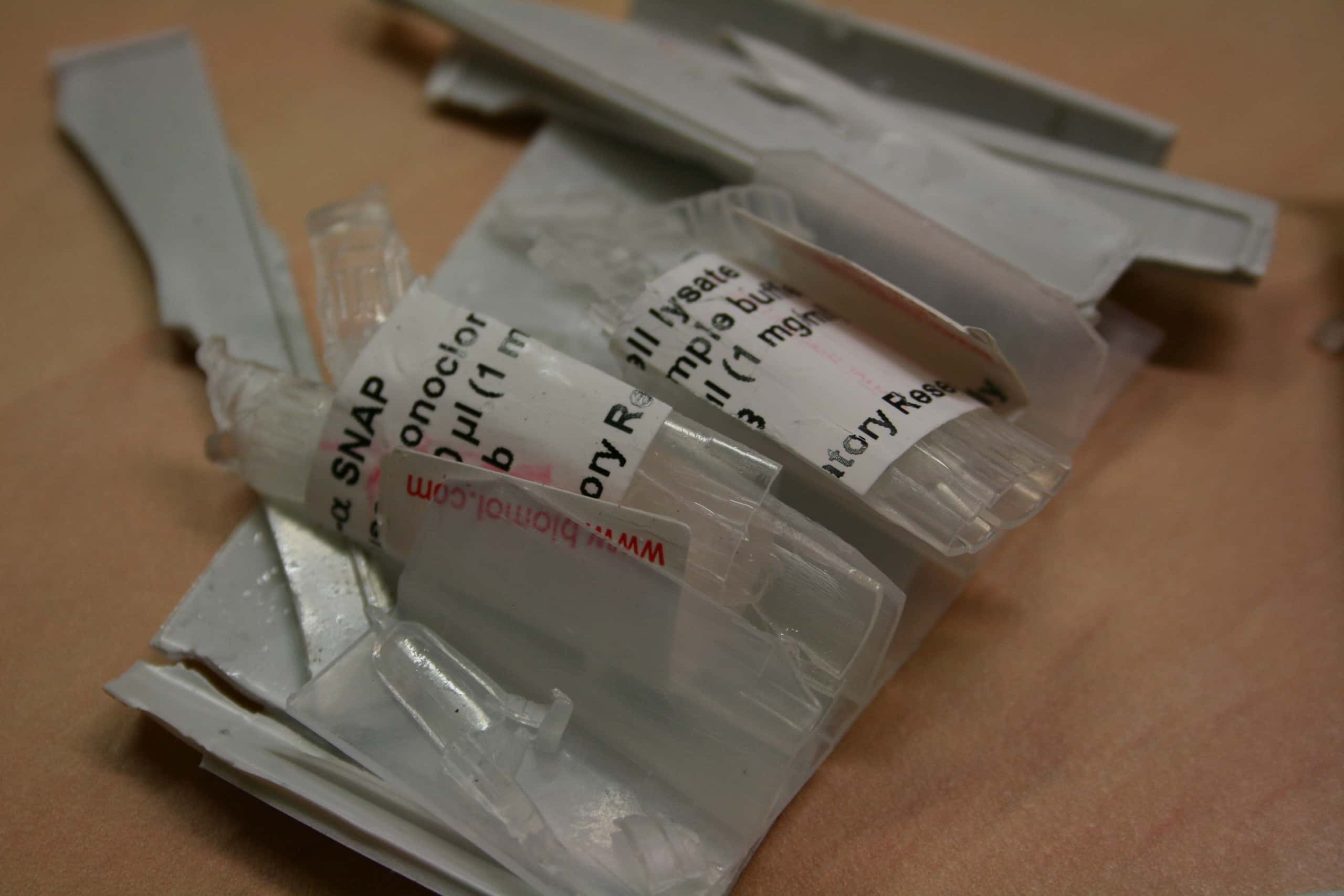

In Amgen, the Supreme Court … held that claims drawn to a genus of monoclonal antibodies, which were functionally claimed, were invalid due to a lack of enablement. The patents at issue (U.S. Patent Nos. 8,829,165 and 8,859,741) concerned a genus of monoclonal antibodies that bind to specific amino acid residues on the PCSK9 protein and block the binding of PCSK9 to a particular cholesterol receptor, LDLR. The claims at issue were functional in that they defined the genus by its function (the ability to bind to specific residues of PCSK9) as opposed to reciting a specific structure (the amino acid sequence of the antibodies in the genus). In affirming the Federal Circuit’s decision, the Supreme Court concluded that the patents at issue failed to adequately enable the full scope of the genus of antibodies that performed the function of binding to specific amino acid residues on PCSK9 and blocking the binding of PCSK9 to the LDLR cholesterol receptor.

The Federal Circuit had provided guidance on the application of enablement to genus claims, holding that

[a]lthough a specification does not need to describe how to make and use every possible variant of the claimed invention, when a range is claimed, there must be reasonable enablement of the scope of the range.

In Amgen, the Supreme Court clarified that

the specification does not always need to ‘‘describe with particularity how to make and use every single embodiment within a claimed class.’’…. Rather, the specification may require a reasonable amount of experimentation to make and use the invention, and what is reasonable will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art. For example, ‘‘it may suffice to give an example (or a few examples) if the specification also discloses some general quality . . . running through the class that gives it a peculiar fitness for the particular purpose,’’ and ‘‘disclosing that general quality may reliably enable a person skilled in the art to make and use all of what is claimed, not merely a subset.’’

The Supreme Court compared the claims in Amgen to the claims involved in the earlier cases of Morse, Incandescent Lamp, and Holland Furniture.

The Court found that ‘‘Amgen seeks to claim ‘sovereignty over [an] entire kingdom’ of antibodies.’’ Similarly,

Morse sought to claim all telegraphic forms of communication, Sawyer and Man sought to claim all fibrous and textile materials for incandescence, and Perkins sought to claim all starch glues that work as well as animal glue for wood veneering.

The Supreme Court further stated that

the more a party claims, the broader the monopoly it demands, the more it must enable. That holds true whether the case involves telegraphs devised in the 19th century, glues invented in the 20th, or antibody treatments developed in the 21st.

The USPTO notes that

These guidelines do not constitute substantive rulemaking and therefore do not have the force and effect of law. They have been developed as a matter of internal USPTO management and are not intended to create any right or benefit, substantive or procedural, enforceable by any party against the USPTO.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.