A case involving photographs of Pablo Picasso’s artwork illustrates how a US court can resolve a dispute involving foreign intellectual property law.

The Ninth Circuit’s decision in de Fontbrune v. Wofsy arose out of a dispute over a “catalogue raisonné” of Picasso’s works.

According to The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms Online, a “catalogue raisonné” is “[t]he complete published catalogue of an artist’s work. Such catalogues … are normally regarded as standard publications on the subject.”

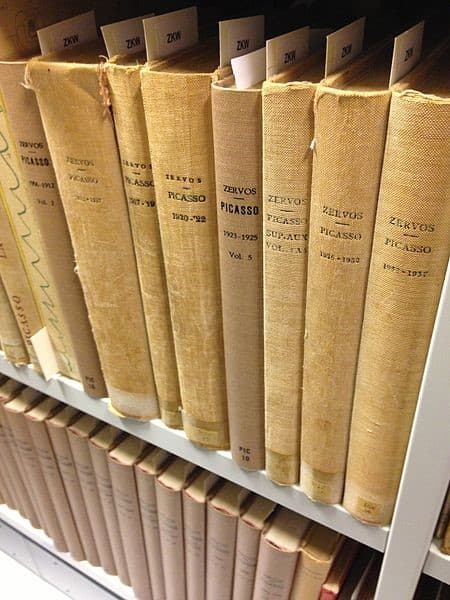

A photographer named Christian Zervos created the catalogue between 1932 and 1970, and it contains 16,000 photographs.

The “Zervos Catalog” is now owned by Vincent Sicre de Fontbrune, a French photographer.

An American art editor, Alan Wofsy, reproduced several photos from the Zervos Catalog in a two-volume work on Picasso.

De Fontbrune sued in a French court for copyright infringement. He eventually won and was awarded an astreinte of two million euros.

De Fontbrune then brought suit in a California district court in order to enforce the judgment.

Under Rule 44.1 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP),

A party who intends to raise an issue about a foreign country’s law must give notice by a pleading or other writing. In determining foreign law, the court may consider any relevant material or source, including testimony, whether or not submitted by a party or admissible under the Federal Rules of Evidence. The court’s determination must be treated as a ruling on a question of law.

The issue in the California case was whether the astreinte from the French court was a fine or penalty (which the California Uniform Recognition Act doesn’t recognize) or a grant of money recovery (which the state does recognize).

The astreinte is a civil law concept that doesn’t have an equivalent in the common law system used in the US.

The Ninth Circuit concluded that the astreinte was comparable to statutory damages under US copyright law.

In making this ruling, the court also had to determine “whether Rule 44.1 authorizes district courts to consider foreign legal materials outside the pleadings in ruling on a motion to dismiss.”

The court concluded that the answer was yes, because a determination of foreign law is a question of law, not fact.

This means, among other things, that a court can do its own research about what a foreign law means and an appellate court can determine that a district court’s research was inadequate.

To receive poetic updates on IP law, sign up for our monthly collection of patent haikus and news here: