A divided Federal Circuit panel has affirmed that three patents owned by American Calcar are unenforceable due to the inequitable conduct of the company’s founder in selectively withholding from the Patent Office certain aspects of a prior art system.

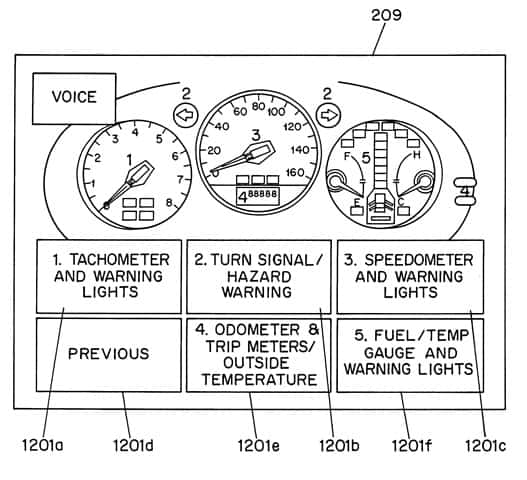

Calcar sued Honda for alleged infringement of fifteen patents, of which three remained at issue at the time of the appeal. The patents involve aspects of Honda’s 96RL multimedia system which was used to display the status of vehicle functions and to search for information about the vehicle. Calcar alleged that computerized navigation systems in Honda cars infringed its patents. On the other hand, Honda asserted that Calcar’s founder, Michael L. Obradovich, deliberately withheld prior art material to patentability from the Patent Office. Obradovich, who had primary responsibility for preparing the patent application from which the other patents derived priority, allegedly failed to disclose information that would have led the Patent Office to deny the patent as anticipated or obvious.

In 1996, when Honda added its navigation system as an option, Calcar was publishing “Quick Tips” condensed from the car owner’s manual. Obradovich had the opportunity to use the Honda navigation system and see and photograph the system and the owner’s manual. Subsequently, Obradovich began work on the patent application that eventually became the original patent at issue. The application referred to the Honda system as prior art, and Obradovich acknowledged that it was the basis for his inventions. However, Honda alleged that Obradovich failed to disclose that the Honda owner’s manual and photos were in his possession and that he deliberately withheld them during prosecution of the patent. Honda asserted that the operational details Obradovich failed to disclose were exactly those claimed in the patents at issue.

The jury found one patent valid and the other two invalid. However, the district court granted Honda’s inequitable conduct motion and found all the patents unenforceable. When Calcar appealed, the Federal Circuit vacated the ruling in part and remanded. On remand, Calcar lost again, then appealed again.

The Federal Circuit Court of Appeals found that Obradovich’s disclosures to the Patent Office excluded material information and showed deceptive intent. According to the Court, to determine if the information omitted is material, the Court must ask if the PTO would not have allowed a claim had it been aware of it. On the other hand, intent may be inferred from indirect and circumstantial evidence considering that direct evidence of deceptive intent is rare.

In applying the concept of materiality, the Federal Circuit held that the only difference between Honda’s 96RL system and what Calcar actually claimed was “the nature of the information contained in the systems”: navigational details (destinations, addresses, directions) in the 96RL system and information about the vehicle itself as shown in the patents. Thus, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the PTO would have not allowed the patents as “it would have been obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art to include different information in the 96RL navigation system.”

In determining deceptive intent, the Federal Circuit likewise affirmed the findings of fact by the district court which determined that Obradovich possessed material information based on his own testimony about his personal knowledge of the 96RL system, test drives of the 96RL with the system, and use of figures from the 96RL owner’s manual in the patent application he drafted. Obradovich knew the information was material because he himself acknowledged the importance of the information he possessed about how the 96RL system was used to access information and present it to the user. Thus, single reasonable inference based on the facts regarding Obradovich’s role in developing the patent application was that he deliberately decided to withhold the information from the PTO. Partial disclosure of material information about the prior art to the PTO cannot absolve a patentee of intent if the disclosure is intentionally selective.

Considering the matters discussed, it may be concluded that while it may be tempting to an inventor to try to hide relevant prior art from the Patent Office, such a misguided “strategy” can lead to wasted years and millions of dollars in litigation expenses before the patent owner’s misconduct is finally uncovered.