The US Supreme Court has issued its decision in the important copyright law case of Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al.

We previously discussed this case here.

In 1981, Lynn Goldsmith, a professional photographer, was commissioned by Newsweek to photograph a then “up and coming” musician named Prince Rogers Nelson (commonly known as “Prince”).

Years later, Goldsmith granted a limited license to Vanity Fair to use one of her Prince photos as an “artist reference for an illustration,” for “one time” only.

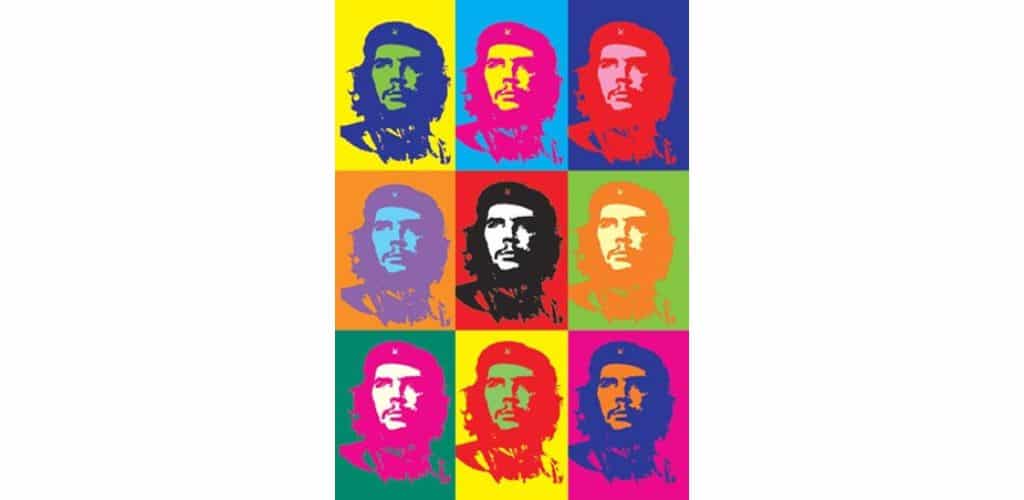

Artist Andy Warhol used Goldsmith’s photo to create a purple silkscreen portrait of Prince, which appeared with an article about Prince in Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue. The magazine credited Goldsmith for the original photograph and paid her $400.

Warhol, without a license from Goldsmith, made a series of other silkscreen portraits of Prince based on Goldsmith’s photo, with various color schemes. In 2016, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF) licensed to Condé Nast for $10,000 an image of “Orange Prince” for the cover of a magazine commemorating Prince after his untimely death.

Goldsmith didn’t know about Warhol’s “Prince Series” until 2016, when she saw the magazine cover. She notified AWF that she believed the works infringed her copyright. AWF then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement or, in the alternative, fair use.

A district court found for the AWF, but the Court of Appeals reversed.

The four factors that courts apply in determining whether unlicensed use of a copyrighted work is “fair use” – and thus not a copyright violation – are:

- the purpose and character of the use,

- the nature of the copyrighted work,

- the amount and substantiality of the portion taken, and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market.

The issue before the Supreme Court was:

whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” … weighs in favor of AWF’s recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast.

When determining whether a new work based on a prior copyrighted work is infringing, courts consider whether the new work is merely derivative (and thus infringing) or whether it’s “transformative,” and thus allowed under the doctrine of fair use.

For example, parody has been held to be transformative and thus fair use.

As the Court noted,

AWF contends that the Prince Series works are “transformative,” and that the first fair use factor thus weighs in AWF’s favor, because the works convey a different meaning or message than the photograph. But the first fair use factor instead focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism.

The Court noted that

The commercial nature of a use is relevant, but not dispositive. It is to be weighed against the degree to which the use has a further purpose or different character.

The Court concluded:

the purpose of the Orange Prince image is substantially the same as that of Goldsmith’s original photograph. Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince. The use also is of a commercial nature. Taken together, these two elements counsel against fair use here.

Justice Kagan filed a dissenting opinion, calling Warhol “the avatar of transformative copying.” She concluded that the majority’s opinion

will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.

The majority’s opinion is likely to be highly influential in cases about whether generative AI – such as Midjourney and ChatGPT – can legally copy and adapt unlicensed intellectual property owned by others, as we discussed here.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.