The US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit has affirmed a lower court’s entry of summary judgment against the plaintiff in a case of an alleged infringement of floor plans, finding that only a virtually identical design would infringe the plaintiff’s “thin copyright.”

The case of Design Basics, LLC v. Signature Construction, Inc. involves a plaintiff that the court bluntly describes as a “copyright troll”:

The firm holds registered copyrights in thousands of floor plans for suburban, single-family tract homes, and its employees trawl the Internet in search of targets for strategic infringement suits of questionable merit. The goal is to secure “prompt settlements with defendants who would prefer to pay modest or nuisance settlements rather than be tied up in expensive litigation.” … As we explained in Lexington Homes, “[t]his business strategy is far removed from the goals of the Constitution’s intellectual property clause.” …. Instead, it amounts to an “intellectual property shakedown.”

The plaintiff has filed more than 100 similar lawsuits in the past ten years.

As the court notes, the Copyright Act lists various categories of work that qualify for copyright protection. These include “literary works,” “musical works,” “dramatic works,” and “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works.”

“Architectural plans” and “technical drawings” are included in the statutory definition of “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works” and thus can be copyrighted in this category.

In 1990, the following definition was added to 17 U.S.C. § 102(a)(8):

An “architectural work” is the design of a building as embodied in any tangible medium of expression, including a building, architectural plans, or drawings. The work includes the overall form as well as the arrangement and composition of spaces and elements in the design but does not include individual standard features.

One important limitation for copyright protection for architectural works is known as the “idea/expression dichotomy”— “the line that separates copyrightable expression from non-copyrightable ideas and facts.”

As the court explained,

Merger doctrine prevents the use of copyright to protect an idea or procedure. If an idea or procedure can be expressed in only a few ways, it is easy to copyright every form in which the idea can be expressed, indirectly protecting the idea itself.

Works of authorship are protected under copyright law. However, the ideas expressed in those works are not, as the US Supreme Court explained in the 2021 case of Golan v. Holder:

In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.

In order to establish copyright infringement, as the Supreme Court has explained, the plaintiff must establish two elements:

1. ownership of a valid copyright, and

2. copying of constituent elements of the work that are original.

In this case, the plaintiff’s registration of the copyrighted plans at issue was not contested.

The second element also turns on two questions:

The first question is whether, as a factual matter, the defendant copied the plaintiff’s protected work (as opposed to independently creating a similar work); the second question is whether the copying “went so far as to constitute an improper appropriation.”

“Proof of copying by the defendant is necessary because independent creation is a complete defense to copyright infringement,” as courts have noted. For “[n]o matter how similar the plaintiff’s and the defendant’s works are, if the defendant created his independently, without knowledge of or exposure to the plaintiff’s work, the defendant is not liable for infringement.”

Copying can be shown either directly or indirectly. An indirect or circumstantial case of copying can be proven with

(1) evidence that the defendant had access to the plaintiff’s copyrighted work (enough to support a reasonable inference that the defendant had an opportunity to copy); and (2) evidence of substantial similarity between the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work (enough to support a reasonable inference that copying in fact occurred).

However,

Standard elements in a genre—called scènes à faire in copyright law—get no copyright protection. Scènes à faire is “so rudimentary, commonplace, standard, or unavoidable that they do not serve to distinguish one work within a class of works from another.”

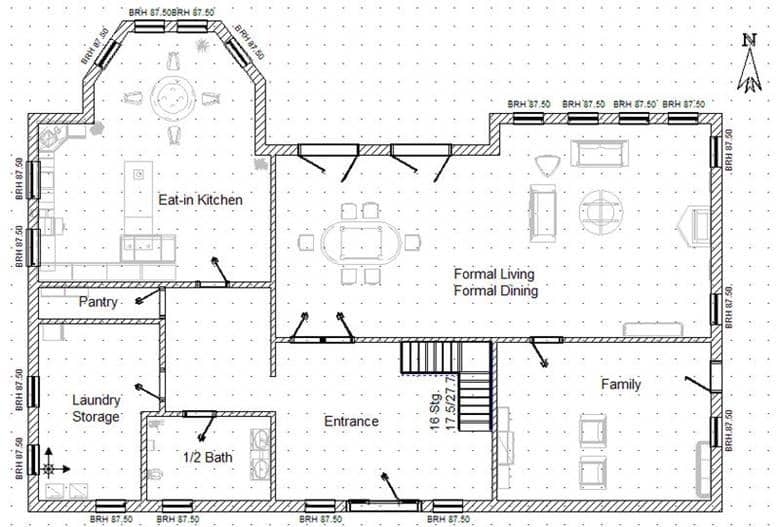

The court had previously held that the plaintiff’s plans consisted largely of scènes à faire:

Every plan has a kitchen, a great room or living room, a dining room, bedrooms, bathrooms, and so forth. The arrangements of the rooms are also largely scènes à faire. The kitchen is always close to the dining room; the bedrooms will usually be clumped together and near a bathroom; the door from the garage into the house usually leads to the kitchen rather than the great room or living room.

These arrangements exist for practical purposes; they represent “ideas” about what makes a house functional. Under the merger doctrine,

To guard against this kind of overprotection, when an idea can be expressed in only limited ways, courts say that the expression “merges” into the idea and cannot receive copyright protection.

Thus, held the court,

in this particular architectural genre in which copyright protection is thin, proving unlawful appropriation takes more than a substantial similarity between the plaintiff’s work and the defendant’s work. Instead, only a virtually identical plan infringes the plaintiff’s copyrighted plan.

The court thus agreed with the district court that the defendant’s plans were dissimilar enough to preclude liability for copyright infringement.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.