As the New York Times reported, President Biden has announced that he’s pushing federal regulators to limit non-compete clauses in contracts as part of an effort to bolster competition in the economy.

On July 9, President Biden signed the Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy. One clause states that

To address agreements that may unduly limit workers’ ability to change jobs, the Chair of the FTC is encouraged to consider working with the rest of the Commission to exercise the FTC’s statutory rulemaking authority under the Federal Trade Commission Act to curtail the unfair use of non-compete clauses and other clauses or agreements that may unfairly limit worker mobility.

According to the Times, employers have increasingly used non-competes in recent years to try to inhibit their workers’ ability to quit for better jobs.

The Fact Sheet accompanying the Order notes that

Tens of millions of Americans—including those working in construction and retail—are required to sign non-compete agreements as a condition of getting a job, which makes it harder for them to switch to better-paying options.

The Order encourages the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to ban or limit non-compete agreements. However, it’s not clear exactly what the President is asking for or how the FTC will respond.

As the National Law Review explains,

It remains unclear what the ultimate scope of the FTC’s rule will be, especially in light of the inconsistent messaging by the White House. Indeed, the Fact Sheet calls for the FTC to consider a “ban” on non-competes, the Order simply calls for the FTC to “curtail the unfair use of non-compete clauses,” and statements by the White House in the wake of the Order suggest that it is really aimed at preventing the use of non-competes with blue collar workers and low wage employees. The use of the term “unfair” in the Order is certainly a nod to the FTC’s authority under Section 5 of the FTC Act to prohibit “unfair methods of competition.” Since 2015, the FTC’s policy has been to treat its authority to prevent anticompetitive conduct under Section 5 as no broader than under the Sherman Act, but in a 3-2 vote, it withdrew that policy on the same day the Executive Order was issued. This frees the FTC to take action against conduct that may not violate the antitrust laws (possibly including some types of non-competes), at least unless and until the courts rule otherwise.

As the Times reported several years ago,

The growth of noncompete agreements is part of a broad shift in which companies assert ownership over work experience as well as work. A recent survey by economists including Evan Starr, a management professor at the University of Maryland, showed that about one in five employees was bound by a noncompete clause in 2014.

That number has since significantly increased in the past few years. According to the Fact Sheet,

Roughly half of private-sector businesses require at least some employees to enter non-compete agreements, affecting some 36 to 60 million workers.

The Economic Policy Institute estimated in a 2019 report that the number of workers subject to non-competes is around 28% to 47% of all private-sector workers.

The purpose of non-competes isn’t supposed to be to actually restrain competition in general – since competition is considered a good thing in a capitalist economy. Rather, non-competes are often intended to protect employers from unfair competition when ex-employees use their intellectual property and confidential information to benefit their competitors. However, employment contracts can accomplish that without overly restricting employees’ future employment opportunities.

A number of states already ban or limit the use of non-compete clauses in employment contracts. California, North Dakota, Oklahoma and the District of Columbia ban such clauses outright. About a dozen states forbid them for certain kinds of low-wage workers, who are less likely to have access to confidential or proprietary information.

As The Conversation reports,

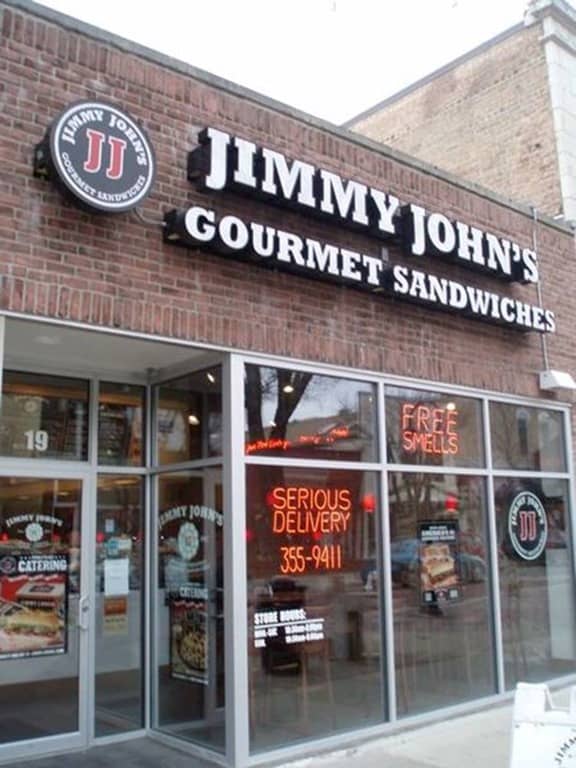

“By locking low-wage workers into their jobs and prohibiting them from seeking better-paying jobs elsewhere, the companies have no reason to increase their wages or benefits,” Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan said when she sued the Jimmy John’s fast-food franchise in 2016 for making its employees sign noncompete clauses.

The chain subsequently agreed to drop its noncompetes, which had also come under fire in New York. The clauses had barred the sandwich maker’s workers from working for other companies that earn more than 10% of their revenue from “submarine, hero-type, deli-style, pita, and/or wrapped or rolled sandwiches” for two years after leaving the Jimmy John’s payroll.

Certain other states, such as Georgia and Idaho, are moving in the opposite direction and making it easier for employers to enforce non-competes.

The Conversation notes that

Given the patchwork of state laws – and reports that companies are using noncompetes even in places where they are banned – a uniform federal rule could clarify the situation and benefit both employees and employers.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.