Dozens of musical artists have expressed their objections to the Trump Campaign’s use of their music at events.

According to Wikipedia, at least 35 musicians have opposed Trump’s use of their music.

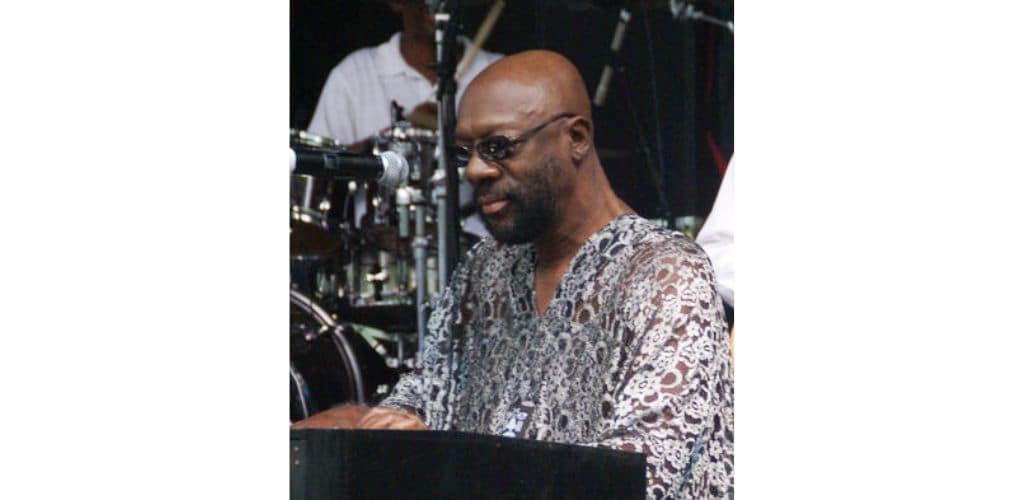

Recently, the family of the late singer-songwriter Isaac Hayes (shown above), along with Isaac Hayes Enterprises, published a letter claiming unauthorized use of the Hayes song “Hold On (I’m Coming)” at Trump events and in online videos. The letter claims that this happened at least 134 times, despite the protests of the copyright holders over several years.

The letter alleges that this unlicensed use of music violates Title 17 USC, including section 501 of the US Copyright Act.

The letter demands payment of $3 million for a license fee and asks that the campaign make an official statement that the previous use of the music wasn’t authorized.

The letter noted that the normal penalty for such copyright infringement would start at $150,000 per use (more than $20 million total) if the case goes to court.

Also recently, Canadian singer Celine Dion’s management team and record label posted a statement to X (formerly known as Twitter) stating that she didn’t authorize the Trump campaign’s use of her song “My Heart Will Go On,” from the movie Titanic.

The post included the note “…And really, THAT song?” perhaps in reference to the movie being about a sinking ship.

ASCAP, a leading music licensing entity, notes that

Music possesses a unique power to inspire, motivate and energize a campaign. And music has been used in campaigns since the founding of our country. George Washington effectively used “God Save Great Washington” (a parody of “God Save the King”), Franklin Roosevelt used “Happy Days Are Here Again” (written by ASCAP members Milton Ager and Jack Yellen), Dwight Eisenhower used “They Like Ike” (written by ASCAP founding member Irving Berlin) and President Barack Obama used “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours” (written by ASCAP member Stevie Wonder) just to name a few of the Presidential campaign success stories.

If a campaign wants to use copyrighted music at events, in ads, in social media, or otherwise, it must obtain a license. ASCAP explains that

while many venues have proper “public performance” licenses, as a general rule the ASCAP licenses for convention centers, arenas and hotels exclude music use during conventions, expositions and campaign events. If a campaign is holding many events at dozens of different venues, it may be easier for the campaign itself to obtain a public performance license from ASCAP (and possibly the other US performing rights organizations if the music is licensed through one of them). This license is issued to an individual candidate’s specific campaign and extends only until the candidate is sworn into office — not for the candidate’s full term in office. Having such licenses in place would guarantee that, no matter where you have a campaign stop, the performances of music at the events would be in compliance with copyright law

Also, even if the music has been properly licensed, ASCAP says that a campaign can still potentially be sued based on causes of action other than copyright infringement. Such a suit could potentially be brought based on:

- The artist’s Right of Publicity, which in many states provides image protection for famous people or artists;

- The Lanham Act, which covers confusion or dilution of a trademark (such as a band or artist name) through its unauthorized use; or

- False Endorsement, where use of the artist’s identifying work implies that the artist supports a product or candidate.

For example, as USA Today reported,

Trump took to his social media platform Truth Social and posted several suspected artificial intelligence-generated images alluding to Taylor Swift and Swifties’ support for his campaign, despite the singer vocalizing disdain for the Republican nominee in the past.

As ASCAP notes,

As a general rule, a campaign should be aware that, in most cases, the more closely a song is tied to the “image” or message of the campaign, the more likely it is that the recording artist or songwriter of the song could object to the song’s usage by the campaign.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.