Since it’s an election year, you can pretty much count on musicians getting upset when politicians use their music.

As we discussed in this blog from 2015, in the last presidential election Neil Young objected when then-candidate Donald Trump used his “Rockin’ in the Free World” for the launch of his campaign.

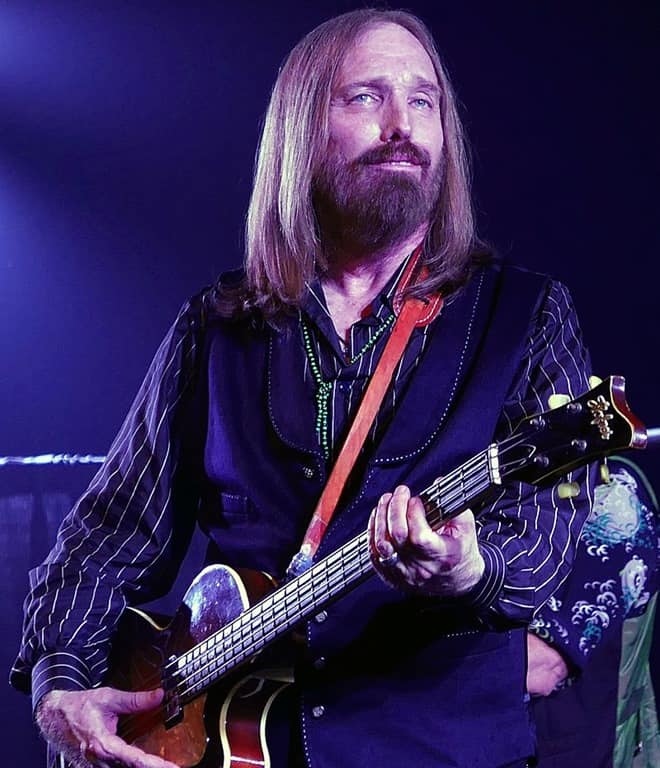

This time, the estate of the late rocker Tom Petty sent the Trump campaign a cease-and-desist letter over its use of the song “I Won’t Back Down” at a recent campaign rally.

A recorded song has two separate copyrights:

-

- One protects the song itself – the music and the lyrics (if any)

- Another protects the performance of that song

Often, but not always, the song and the performance will be separately owned – the song by the songwriter(s) (or his/her/their music publishing company) and the performance by the record label that released the song.

Under US copyright law, the copyright holder has the right to authorize – or prohibit – the public performance of a copyrighted work such as a song, including a recorded performance of the song.

If you play recorded music in a store, restaurant, or bar, or at a public event like a conference or political rally, you’re supposed to obtain (and pay for) a public performance license.

There’s generally no need to track down the individual rights owners, because most music is licensed in the US via one of the following performing rights organizations:

-

- ASCAP

- BMI

- SESAC

- GMR

Obtaining a license costs from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars per year, based on factors like the size of the venue. Many large venues, such as convention centers, have their own blanket licenses, so that groups hosting events don’t have to worry about licenses.

However, these blanket licenses may not cover political events. ASCAP offers a special Political Campaign License agreement, and ASCAP members can ask that specific songs be excluded from the license to a specific campaign.

The performing rights organizations do check up on venues, and penalties can be up to $30,000 for each song, or up to $150,000 if the infringement was willful.

For example, in 2016 a New York steakhouse was ordered to pay $16,000, plus the plaintiff’s attorney’s fees and costs, for playing five songs without a license.

In addition to copyright law, politicians need to worry about running afoul of the artist’s right of publicity and claims of “false endorsement” that may be implied by the association of a song with a politician.

Just like the haiku above, we like to keep our posts short and sweet. Hopefully, you found this bite-sized information helpful. If you would like more information, please do not hesitate to contact us here.